A media storm has erupted surrounding the story of 27-year-old British Barrister, Charlotte Proudman, who asked senior solicitor Alexander Carter-Silk (aged 57) to connect on LinkedIn. He replied by commenting on her “stunning picture” and awarded her “the best LinkedIn picture I have ever seen.” She replied to tell him she considered his response “unacceptable and misogynistic behavior” and then tweeted an image of his LinkedIn message for the whole world to see.

The exchange was amplified by the UK’s second biggest-selling daily newspaper, the Daily Mail (a tabloid), running a photo and headline of Proudman and labeling her a “Feminazi.” Without using the same ugly label, Proudman critics have questioned the proportionality of her response in her public shaming of the older man.

On the other side, Proudman supporters have stepped forward indicating she should be applauded as she was right to call out sexism -- and that she did a favor for all women by making her exchange with Carter-Silk public so that others will be careful when building professional relationships.

I think the various sides of the debate are missing a key point – that the boundaries of acceptable behavior on today’s social media platforms are loosely governed by user etiquette and user agreements. Unless the use of a social media platform is officially sanctioned by your employer -- and you’re interacting only with fellow colleagues -- there’s no guarantee you won’t encounter behavior on LinkedIn any different than you might find on any other openly accessible social media platform -- such as Facebook or even Ashley Madison.

While Carter-Silk’s message to Proudman seems buffoonish to me, I think his original sin is that he responded to an invitation request from someone he’d never met in the first place. Proudman may consider LinkedIn an extension of her corporate intranet and let that govern her behavior -- while Carter-Silk may consider LinkedIn no different than the Tinder app. LinkedIn, like other social media platforms, is simply a filter to others in the world at a large so it’s “user beware” when applying this filter.

In fact, without first having real world interaction before proposing or accepting an initial LinkedIn connection request, people are not only at risk of mismatched expectations governing mutually acceptable behavior, they can’t even be sure the other person is even real.

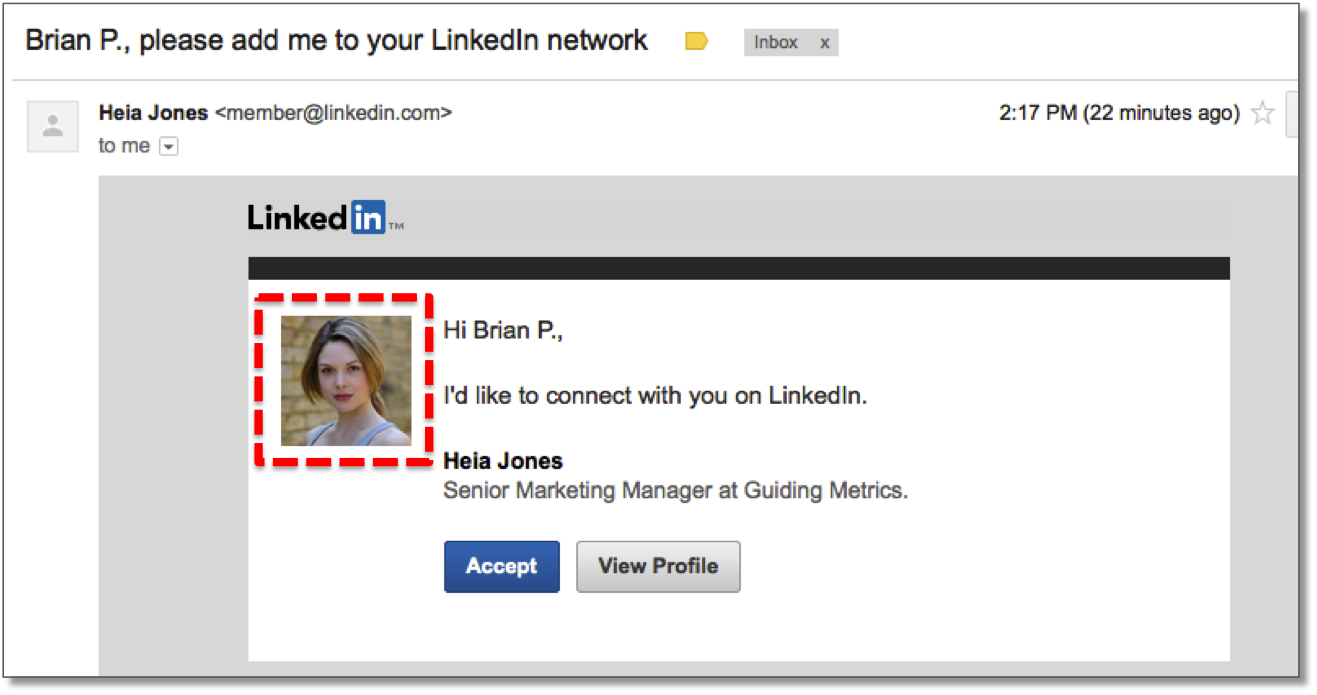

I’m not alone in receiving numerous connection requests on LinkedIn from people with fraudulent profiles. For example, the image associated with this invitation request -- from “Heia Jones” is clearly fake:

Heia, a "Senior Marketing Manager at Guiding Metrics," may be a real person (although I doubt it) -- but a Google image search indicates that her profile photo was previously listed as one of “the most beautiful women on Flickr” -- and it is even called out by one social media blogger (link: http://kschang.hubpages.com/hub/How-to-choose-your-Profile-Photo-for-Social-Media-a-list-of-dos-and-do-not-dos) as a example of a photo NOT TO USE when building a profile. Apparently “Heia” missed that article.

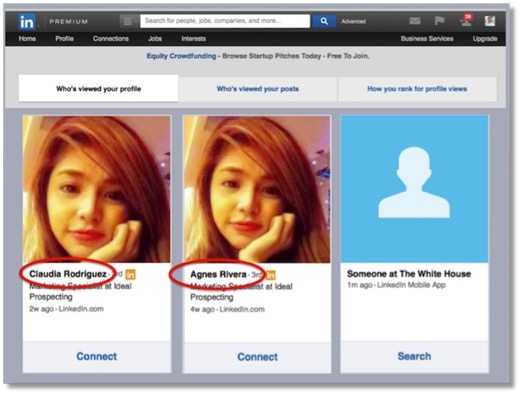

Another example: By using LinkedIn’s “Who’s viewed your profile” feature, I can see that my profile has been visited by “Claudia Rodgriguez” and then later “Agnes Rivera” – both from the same company (“Ideal Prospecting”) and the profile image of each person is exactly the same. Really, “Ideal Prospecting” -- you want me to trust that this person (or your company) is credible?

Career experts might caution that you should be careful not to connect with someone over LinkedIn that you’ve never physically met -- but that would eliminate the opportunity for many people to connect with potentially useful contacts, recruiters, or headhunters. Others recommend you just visit a requestor’s profile and use your judgment -- but with enough requests coming in, that could be a huge time sinkhole and there are scammers that could be highly sophisticated in their deception.

My rules for responding to connection requests are simple. I won’t accept a connection request if we haven’t first: 1) talked by phone, 2) met in person, or 3) been introduced by someone I trust. It’s not a perfect system, but it’s efficient. At the same time, I do make myself openly available for (paid) phone calls through my ECN Profile - which someone can also find via an ECN Badge on my LinkedIn profile.

ECN Badge

After an ECN call -- even for as little time as 15 minutes – I’m more prepared to accept a connection request. Consider it a secondary filter that sits on top of my LinkedIn profile - and an excellent one at that. It’s especially effective as a filter to screen out sales reps (Warning: sales reps may become a little indignant about having to pay to pitch their wares – but I think it is fair).

Real world interaction in-person or by phone and prior to making or accepting a LinkedIn connection request, is a great way to help ensure authenticity of another person’s identity and to make sure you have a common expectation on how to use this very powerful social media platform we call LinkedIn.

So Heia, Claudia, Agnes (and if I were ever to get a connection request from you too Charlotte Proudman), if you’re authentic and sincere, don’t take it personally that I’ll ignore your connection request. It has nothing to do with your profile picture, your job title, or anything else in your LinkedIn profile. I’m just working to ensure that my digital experience on LinkedIn reflects my real world experience and I recommend that others do the same.

Note: Brian Christie is the CEO of Brainsy, Inc. and can be reached for phone discussions via his ECN Profile. If you'd like an ECN Badge, you can find instructions for registering here.

Register for FREE to comment or continue reading this article. Already registered? Login here.

0

Great read, Brian.

Thanks for sharing !!

Steven Burda